There’s an important movement happening in Mississippi, a “new wave” of stories told by filmmakers all over the state. Unfortunately, their efforts have yet to be recognized and upheld by the public, our arts institutions, and our government. Even the Mississippi Film Office has not yet done as much as it could for these committed indigenous film directors.

I consider myself lucky to be a small part of this group and I am dedicated to calling more attention to the work of my peers, for it deserves to be given as much weight as any other cinema. This series will highlight the best movies coming out of Mississippi and the insight of the filmmakers themselves about their work.

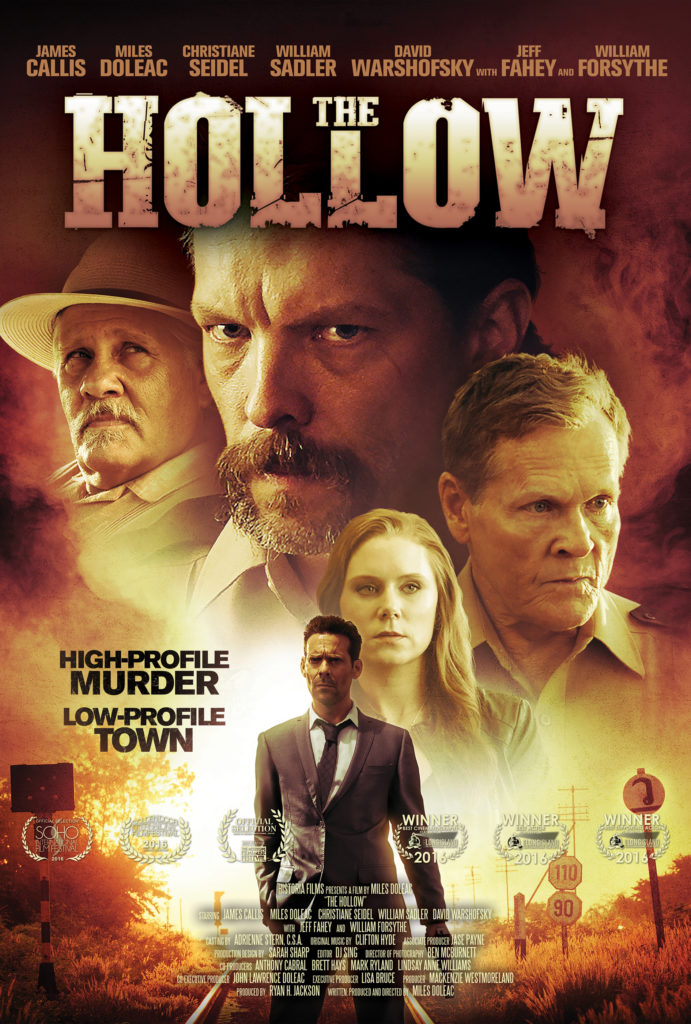

Mississippi in Motion: Miles Doleac and The Hollow

For this first edition of Mississippi in Motion, I chose to interview filmmaker and actor Miles Doleac after studying his film The Hollow. I was stunned that this film has not received more praise and recognition. I hope you will find Miles’ answers and insight into his process as valuable as I do. The Hollow can be seen on Amazon Prime.

Please tell me how you came up with the story for The Hollow.

I had been wanting to write a distinctly southern script, a script set in Mississippi. I’ve long loved Mississippi literature, southern gothic and the like. I think it’s literature that’s rife with dramatic potential. I grew up on Tennessee Williams, Faulkner, Eudora Welty and their works profoundly affected by creative sensibilities. The Hollow‘s Cutler County is maybe my twisted ode to Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County. It was important to me that the film have a very specific sense of place, that the Mississippi setting, the atmosphere, was this tangible force, a character in and of itself. Faulkner’s Mississippi always feels that way.

Too many southern stories have been told by non-southerners and, as a result, many lack authenticity or perspective. Then, Lindsay (my wife) and I were having margaritas one evening with a friend who used to work for a small-town, southern sheriff’s department. Listening to stories about some of the things that went on, I knew I had my frame for what would become The Hollow. I’d been drawn to True Crime as a genre at the time, anyway. I thought the Coens’ No Country for Old Men was masterful. I’d just finished watching season one of HBO’s True Detective, which, to my mind, is probably the best single season of television ever. I started throwing a bunch of ideas at the wall with a decidedly Mississippi-spin and I was, in fairly short order, pleased with what stuck.

What did it take to get this story from conception to script to production?

It was an ambitious project for a second film, especially given the caliber and profile of talent I wanted in many of the roles. It’s the most expensive film I’ve made to date and raising the kind of budget I knew would be necessary to do the script justice was daunting, but I just kept pressing. I was pretty relentless. I pursued potential investors until I was given a hard “no.” Some took months to come through. Thinking back on it now, it was exhausting and, at times, maddening, a little terrifying, but I knew I had to bring this script to life. I remember the day we attached William Forsythe to play “Big John.” His reps asked that we place his salary in escrow and we hadn’t raised the full budget yet. What do you do in that circumstance? Well, if you want William Forsythe in your movie, you put the money in the bank. Being an independent filmmaker, you have to be something of a gambler or a crazy person. You have to just will it to happen sometimes. We weren’t able to cast the character of “Vaughn” until about 72 hours before we were scheduled to start shooting. I’m wrapping up my film festival in Hattiesburg that year and trying to negotiate getting James Callis to sign on, so there I am, going back and forth, from introducing a film or doing a Q & A, then stepping away to talk to an agent or our casting director or James himself. It was harrowing stuff. At the end of the day, though, we landed precisely the right cast, albeit not without some anxiety. Anyway, as I said, it’s our most expensive, most ambitious film, but to date, it has also been our most successful, financially-speaking … so I think we made the right choices in most instances, at least.

Miles Doleac (left) and actor James Callis (right)

As far as the script, the journey of writing Hollow was much different than my first film (The Historian). Three quarters of the script came very fast. Probably in less than month. I had several different ideas about the ending and it took me a while to settle on the right one. I set the script aside for a few months and just let those ideas percolate. When I came back to the script with fresh eyes, not only had the ending become clear, but I was able to add some layers to the characters that I hadn’t thought about before. When I sat back down to work on it again, I finished it in about a week. With The Historian I was noodling away at the thing for a year, tweaking and polishing, in the case of some scenes, right up until the day we shot them. With The Hollow, it was more like jazz. It flew out of me in a couple bursts of inspiration and, when I got up from the computer that second time, it was, more or less, the script we shot.

How does the Mississippi landscape, both rural and urban, effect your story for The Hollow and your other films?

For Hollow, Mississippi’s geography and locations are virtually characters unto themselves. I wanted them to be. I knew they had to be for the film to work. Growing up in Mississippi, I knew these places existed. I wrote to them, I suppose. Even if I had never visited some of our specific locations before scouting, I knew they were there. I had grown up around them or traveled to so many places like them. And, truly, I’m so proud of how these locations came off in the film. Some of them, as shot, are even better than they were as written. They just leap from the screen. I think that’s a testament to their richness. I mean we walked into Magnolia Inn (Hattiesburg) or McDonald’s Store (Hot Coffee) or Dixie Grill (Seminary) and changed almost nothing. These places were real and lived-in and they art directed themselves.

We also shot in the dead of summer and, despite the fact that it was hot as hell, it worked out beautifully. The sweat you see on actors’ faces, on their clothes … it’s real. The make-up team kept wanting to blot the sweat off of actors’ face and I’d constantly have to stop them. I wanted the sweat to be real. The flies are real. Summer heat and humidity in Mississippi is oppressive; it makes you feel like you’re walking in a steam bath sometimes. That climate gave everybody in front of and behind the camera a little edge that was perfect for the film.

Along those lines, how do the culture and people in Mississippi effect your vision as a filmmaker?

Immensely. Mississippi’s in my bones. I believe it’s a place of tremendous creative ferment and by that I mean it’s an inciter to creation. The place, its history and culture … it leans in on you. Makes you want to tell stories. One only need to look at the state’s impressive literary and musical legacy to appreciate that.

Miles Doleac as Ray Everett in a still from the film.

I would consider the film to have a “pulp” feeling to it. Did any pulp crime films or books of the past influence you on this story and production? Also, what other films have most influenced your work?

Absolutely. I’m glad you say that. That’s precisely the feel I wanted. I’ve mentioned No Country and True Detective. I’d add John Sayles’ Lone Star and, even to some degree, David Fincher’s Seven, which deeply impacted me when I saw it in college. That’s a film I still think about often. I just love how grungy it is.

What do you feel is the main difference in directing a veteran Hollywood actor like Sadler or Forsythe and directing a “local” actor who has not worked outside Mississippi?

I would say mostly it’s the ease and familiarity with the medium an actor like Sadler or Forsythe have on set. I mean these guys have been at this a long time. They’re old pros and it shows. They know more about filmmaking than most of our crew probably. I remember when I was shooting The Historian with Sadler, he came up to me at one point and said, “Do you mind if I make a suggestion?” and I said, “Sir, make all the suggestions you want. You’ve been doing this a hell of a lot longer than I have.” Actors like Sadler and Forsythe have an innate sense of what works and what doesn’t at this point. But with guys like that, there’s also an expectation you have to meet, because they’re used to working on much bigger shows. You have to take care of them and be mindful of the fact that they may have just come from Iron Man 3 or Boardwalk Empire. A lot of local actors are just happy to be there, happy to be given an opportunity to stretch their wings. At the end of the day, though, every actor, every personality is a little different. A good director has to be a student of humanity of sorts. You have to know how to talk to people. Being an actor myself, I know what I’d want to hear, what I’d want a director to say to me … so that’s how I approach directing actors. I suppose it’s the “do to others as you’d want done to you” mentality. At least, that’s what I aspire to do.

Doleac (left) working with William Forsythe (right)

Please share your process for developing the character of Ray Everett. What important decisions did you make for this performance in pre-production and during production?

I did not initially write “Ray” for myself. I actually wrote “Vaughn” (James Callis’ character) with a notion of playing him. Then, at some point early in the casting process, Lindsay said to me, “You know, have you ever considered playing Ray instead? I really think you ought to play Ray.” She was absolutely right. I don’t know why I hadn’t seen it from the beginning. I guess I was too close to it. I just kind of slid Ray on. I knew what I wanted him to look like … the mustache, the facial scar … and I knew what I wanted him to sound like. And then I just let nature take its course. I think it’s the most free I’ve ever felt in a film or television role.

What scene was most challenging for you as a director? What scene was most challenging for you as an actor?

As a director, two scenes were particularly challenging: the football game and the finale. The football game was most challenging because we needed so much background. I mean you’re telling a story in a town where football is king and that’s a major plot point, so you gotta get people in the stands. That’s very, very hard on a low-budget indie. We certainly couldn’t afford to pay 300-400 extras, so we had to lure them in other ways. Good catering goes a long way.

Logistically, though, it was the finale. I wanted rain, vomit, gun play, squibs … and we had almost all of our name actors involved. I still can’t believe how well it turned out with a make-shift rain rig and not a powder squib in sight. The squib work was old school, practical, hose work brilliantly executed by Ashleigh Coartney and Ashley Hooker, our hair, make-up, practical effects team. We added a little digital enhancement in post, but most of it was achieved on the day. But we did all that in one beautiful, hellish night, except we didn’t get to Will’s very last close-up, so we had to fake that the next day and even it played seamlessly. I guess the film gods were smiling down on us.

Another still from the film showing Doleac as Ray Everett during the bloody finale.

Acting-wise, I think it was Ray’s opening scene, where he’s being pleasured by a high school girl in his patrol car. I wanted it nasty and uncomfortable as hell. I mean I wanted the introduction of this character to be a gut punch. It had to be just right. And, of course, it’s a tricky thing to play. It’s vile, but we’ve still got to want to follow this character on this journey. I’ve gotten a lot of comments about the scene, some strong responses, positive and negative. So I guess we achieved something. Personally, I think it could have been a little nastier and I wish we had had more time to spend on it.

The look of the film is very distinct. It’s clear that you and your director of photography had a clear idea of how you wanted this story to look. Can you tell us how you came to that decision?

Yeah, two things were musts for me on this. I had to shoot on the Arri Alexa, because I think it’s digital cinema’s closest approximation to film and I wanted to use vintage lenses. We used re-purposed Cook lenses on the film. I love the little imperfections in vintage lenses. I wanted my audience to feel that, even subconsciously. And then I work with the best colorist in the business, Bradley Greer at Kyoto Color, and he, Ben, our DP, and I worked together to achieve this grimy color palette that I think served our story very well.

How do you feel about the reception of the film? What has been the most helpful reaction to the film?

Reactions have been all over the place. And I’m not sure if you ever become completely inured to the negative ones. At the end of the day, too many people have too much time on their hands I suppose when they make it their mission to trash your film on the internet. But then you get these very positive responses too. We had a great review in San Francisco Weekly. Some people have said the film’s too long. I don’t know. I want my audience to get to know as much as possible about the psychology of my characters. I want to have as few “throw-away” or “one-note” characters in my films as possible. And that takes time. As filmmakers, we’re always walking that fine line between giving the audience too much and not enough. I’ve given up trying to figure out what audiences want exactly. I’m just going to do my thing and I hope people, at least the right people, will appreciate it or be moved by it some way.

Doleac and crew with William Sadler (right) on set.

Along those lines, how did you expect Mississippi audience members to react to the film and did the results confirm or defy those expectations?

Almost uniformly positive as far as I can tell. Look, for me, Mississippians need to be telling our stories, even the ugly ones. And, of course, there’s a lot of ugliness in The Hollow. But it’s more complex than that. I think Mississippi is a beautiful and complicated place and I think The Hollow shows that. Folks who are from or have spent any time in Mississippi get that fact. Last night at my film festival, we showed A Time to Kill. There’s a lot of ugliness in that film, but there’s a lot of beauty too. That’s the dichotomy, the razor’s edge that makes Mississippi such a rich, creative place. But you have to be here. You have to know the soil and the people to truly understand what this place is about.

As filmmakers we all have things we might want to change about our films if we could do them all over again. If you feel comfortable, can you share with us one thing you might do differently with The Hollow if you made it today?

What’s the old saw? You never finish a film. You abandon it. There are lots of things I would have done differently, but also lots of things that work in my view. Two things that immediately spring to mind. There are no referees in our football game scene. I had made it known that I wanted them, but I didn’t insist on it and it just fell through the cracks. It always bothers me when I watch the scene now. How many audience members notice? Who knows? The other is the opening sequence. I would have given it more time. It’s so close to precisely what I had envisioned, but not quite there, but we just ran out of time. We had to cut some shots. We had to move. The first five minutes of any movie are so important, but time is the great enemy of the independent filmmaker, because you don’t have the luxury of buying more of it.

Great interview! I really enjoy hearing how independent filmmakers are able to bring their films to life, get big name stars, and give new actors big roles in their films!