No Rest for the Wild

A Look Back at 2017

I’d be lying if I said it isn’t hard to look back on this year and put it in perspective. But these words now are important however subjective they might be, if only to be read years down the line by me or anyone else.

2017 has been the roughest year for Running Wild. I am not exaggerating when I say that we were in a handful of life or death situations, on and off set. And that was just one aspect of the challenges we faced. But here we are, still alive and moving into 2018.

Horror Films, Festivals, and Flipping the Truck

The year began with an immediate production. I’d optioned the short story Bride of Violence by Lawrence Block years before and had to April 2017 to start shooting or I’d lose it. So with a very small budget, we ventured out to make our first feature length horror film. What ensued on an isolated property near Globe, Arizona I have written about in my Horror Stories blog series. However here is the cliff notes version: our vehicles almost slid off icy mountain roads, we lived off propane with no electricity, cell service or showers for a week, we filmed in old mines (some of which were falling apart) and other locations that posed threats to our safety. Was it worth it? I think so. We did all this with consideration and calculation 99% of the time and got out alive with another feature film in the can.

While filming Bride of Violence in early 2017. Photo by Navid Sanati.

But I felt the team falling apart near the end of the shoot. To their surprise, I recommended we have a little group therapy session: something Travis would never do. We sat in a room and each person on the crew had their chance to share their fears and frustrations from the shoot. You could say there was post-traumatic stress from this experience. Thankfully we mostly got how we felt out in the open. I thought this process was necessary to keep our group a family.

It wasn’t long after Bride wrapped that Navid Sanati and I hit the road with our two dogs for Mississippi. You see, I’d scheduled two feature film shoots almost back to back. By the time Navid and I would be done at the Oxford Film Festival (where his directorial debut Don’t Come Around Here was playing), I’d have approximately three weeks of pre-production before the first day of filming on Blood Country. Yes it was a wild time and it was about to get wilder.

Navid Sanati and myself at the 2017 Oxford Film Festival

We took my ’98 Ford Ranger across the country, towing a camper trailer that we borrowed from my good friend and landlord back in Phoenix. It was a beat up thing, with some reinforcement done before our trip to make it more sturdy. But the thing drove well from Arizona to Oxford. Only a few times along the way did it start to shimmy on the road. It would straighten out and we didn’t think much of it. More on that in a little while.

Neither Navid nor I expected our film to the Best Mississippi Feature award, especially after seeing our competition: The Atoning and Late Blossom Blues. I still feel those movies are superior to ours but I am equally grateful for the recognition we received. The festival was an up and down experience. Without going into much detail, there were romantic complications (good and bad) mixed into our few days near Ole Miss. And my biggest disappointment is that not many people came to see our film. Though we would not benefit financially even if hundreds of people had showed up for Don’t Come Around Here, I felt that the small turnout at three screenings (one even after we won) put a damper on the experience. One thing I would hope for at a festival is for the movie to receive good audience exposure.

When it was all over, we hit the road with the truck and trailer headed to Brookhaven but less than fifty miles on the 55 something happened that has changed my life, the most important moment of this year for me. The camper started to shimmy as it had a couple times, only this instance it kept getting worse and by the time I (behind the wheel) tried to correct it, the trailer was out of control. It swung back and forth on the highway, tearing us off the road into the large grassy median.

The Ford Ranger spun 180 degrees and then flipped over not once but twice. My mom recently asked me what I was thinking when it was turning over. “This is it,” I told her. But it wasn’t. We landed right side up. My instinct was to check for the dogs first (riding in the extended cab together), to see if they were still living. Bongo (Navid’s dog) was okay, panting and probably unaware of how close we’d come to death. I couldn’t find Bandit, my boykin spaniel. I reached down and finally felt the outline of his body under some dirt and blankets. He wasn’t moving. And then suddenly he did and came up from what had covered him in the accident, also clueless as to what had really happened.

No long after the accident. What you see is the remains of the camper.

Behind the truck, the camper was destroyed. As the picture shows, it looks like a tornado hit it. Minus a wall or two that had already been hauled off, that picture represents what we saw right after the wreck. I hung my head on the truck; I felt as if my whole world was gone. Those first few minutes it was very hard to feel happy to be alive. Both our iMacs (used for editing and film business) were in the camper. My projector, which has allowed us to screen at many venues, was in the camper. Our hard drives, housing the footage from ALL our movies, were in that camper! And now it was spread all around the Highway 55 median like a bomb had gone off…

Someone who saw the accident occur had a look at my truck. It was bent up on top, a window busted out, dented in several areas. The two passenger side tires were flat. This person said, “You know, I bet there’s a chance that truck’ll drive if you get some new tires put on.” It hadn’t even entered my mind as a possibility. Drive the truck home? Suddenly a spark of hope lit inside me. The sulking ended and we set out in action to pull out of this ordeal.

After two trips with not one but two tow trucks, the mess that was that camper had been cleaned up. From the wreckage, we salvaged our two computers (packed side by side but found on the ground thirty feet apart so we know they flew), our other equipment and as many odds and ends as we could fit in the bed of my truck. It was packed tight. Back at the shop, they offered to put us up in a hotel. One guy even said we could stay at his mom’s place. Their kindness I will not forget but no, I refused. I was determined to make it back to Brookhaven that night. I had to after all that.

Bongo waiting for us to take off in the busted truck.

Two new tires went on and I got back behind that wheel, no longer straight as it had been. We had no idea if we’d make it but after three hours on the road, we returned to the rural house we rented for Don’t Come Around Here where we would be living again for Blood Country. The next day I took the truck to a mechanic place in Brookhaven to have it looked over. The guy told me the truck was all bent up underneath. “Either sell it now for 500 bucks if you’re lucky or drive it till it won’t go no more. Just change the oil,” he said. My good friend at the time, on the other hand, told me there’s no way it would keep driving, that I should get rid of it. Since then, I have driven my Ford Ranger all around Mississippi, to Texas and from there Arizona and back to Mississippi, down to the coast to make Cornbread Cosa Nostra, to Arizona again and Colorado and now as I write this back to Arizona. It’s a survivor, like we were that day. More on what that day and the truck mean to me at the end of this…

There Could Be Blood

For twenty days in March/April of 2017, we produced a Western, our first true period piece. The budget of Blood Country was a little over fifty thousand dollars. That may not sound unusual to those unfamiliar with the cost of making a feature film, least of all a Western, but it is incredibly low by comparison to how most of these films are made.

The three weeks that led up to the shoot were packed with location scouting and the organization of every possible detail I could sort out. My goal was to figure out food, lodging and other elements for the first week of production until my team from Arizona came in to lend a hand on the producing side. This method and the limited time set us up for a game of chase, as we fought to work ahead for the follow week or even day, throughout production.

I underestimated how much travel would factor into this film. We drove all over Mississippi: from the North East (Corinth), to the Delta (Greenwood), to out of the way places (Rodney) and the list goes on. No matter what, there was at least a thirty minute drive at the beginning and end of each day. Many times there was a hike away from our vehicles into the woods to reach a cabin or spot we’d picked out. I say all this to give you an idea of the exhaustion of resources and energy that we faced on this film. I love such challenges but I believe it started to wear on us.

Some of our crew halfway through production on Blood Country.

Though I think Blood Country is the best film I’ve directed to date, it was my least favorite film to make. There were great moments on set. There were excellent collaborations. For instance, Nick Fornwalt (director of photography) and I worked together better than ever. Cotton Yancey was challenged with a lead role and he exceeded all expectations, even my own. Chris Bosarge, our other leading man, was a champion of endurance. The rest of the cast delivered for the most part. But the team did not come together as I hoped. In fact, it fell apart.

Over the course of twenty days, I felt a rising negativity among some of the crew. Along with this, things started to spread out. At the center of production were Nick and I, along with our assistant director, sound man, gaffer and grips. Many of the others began to distance themselves from the action (and me). After producing over ten feature films, I finally realized how important proximity is, to this filmmaker at least. Let me try to explain. As I mentioned, at the center of each of our films there has been a machine. It usually consists of the cinematography, sound mixer, lighting technician and myself. This machine, this wheel, is constantly working, always turning; it is in motion from the start of the day to the finish. However, there are other pieces (people) in this process who aren’t part of the machine and seemingly don’t want to be. They hang on the outskirts, coming in to do work then retreat until they are called on to do more. Next to the wheel, there is no way to not be swept up in our motion. Now I ask this in all sincerity: if you’re making a movie, why would you not want to be at the center of what’s happening? Why would you not want to be as much a part of it as you could be?

This is the wheel at the center of production. Photo by Dania Blanco.

On Blood Country, I saw that the people who worked the least, the ones who had the worst attitudes on set, kept their distance. They were not connected. They were not in the heart of this movie. And eventually, that hurt the production as a whole. I have always struggled with the ability to let a crew member go. Firing one of the team on a minuscule budget like ours means that I or someone else would have to accept their responsibilities; it isn’t realistic to find another person halfway through shooting and piling more work on people who already work their asses off just isn’t right. But this wasn’t and isn’t how I want to make a film.

I mention all this only not to be negative. It is part of this year, part of our history as a company and so I think it should be said. Blood Country was an incredible achievement for us, for me, on so many levels and I am quite proud of what we created. But I left that production on April 4th with a desire to revolutionize the way our crew works, the way our set runs, and to find a positive way to make movies together.

The Band Breaks Up

The period between productions is limbo for me. I have no great love for post (editing, sound mixing) compared to my passion for being on set. Not long after we wrapped the Western I traveled to Colorado where my parents now live and where I’d produced The Curse of the Dragon Sword at the tail end of 2016. The film premiered in early May. For the first time I sat in the theater to watch a movie I’d been a part of but had very little idea of how it turned out. The experience was joyous. The movie is fun, funny and just a great time. I was quite proud of Jason Phelps for putting it all together and that I was a part of the process.

Director Jason Helps before the Dragon Sword premiere in Colorado.

From Colorado I traveled to Arizona to pack up my things. You see, I was living in two places (there and Mississippi) and spending more time in the latter. I decided by necessity I needed to live in the South through the end of 2018 when our slate of four films would be complete. Though this move was sure to increase the suspicion that I had given up on work in Arizona, I went back to my little house in Phoenix, sold what I could, gave away the rest and filled the bed of my truck with everything I owned. It’s impossible to predict or change what people think. Some believe I abandoned Arizona. Others suspect I fled from the state because of increasing unpopularity. Neither are true. I am as much an Arizona filmmaker as a Mississippi one. In fact, I belong wherever the movie is being made and at the same time I belong nowhere. Right now something important is happening in Mississippi. There’s a movement: actors are passionate, audiences are eager to see local stories told, and our movies are getting made. I will be back to Arizona again and again to make films here.

I packed only what could fit in my truck bet and moved to Mississippi.

By the time I settled in Mississippi, Running Wild Films was not the same company it had been at the beginning of 2017. For one reason or another, the team I had built over the years completely dissolved. Whether they left because I asked them to or of their own volition, a company of five became a team of one. Of course, Gus Edwards was with me still. He has always been my advisor, a steady backbone for Running Wild. And from the rubble, my long collaboration and friendship with James Alire remained intact, perhaps stronger than ever. There are also a few freelancers that I can always count on, namely the two cinematographers I work with: Nick Fornwalt and Jared Kovacs. But in terms of those involved with the daily affairs of Running Wild, I am on my own now and perhaps it is for the best. I don’t think I will place the same emphasis or devote as much energy to building a “team” again. It may be best to work with free agents, people who have their own companies specifically. We shall see. Who knows where this journey of film will lead me.

One new voice in our work did emerge in this limbo period. Tony Pellum, who had worked on the crew of Durant’s Never Closes, took over post-production on Bride of Violence and saved the movie. The cut was in terrible shape. Tony came in and brought a fresh perspective to what we shot, surprising both Jared (director of photography on that film) and me. Though we are still in the process of polishing the film for release, I credit its current state and survival to Tony.

Also during this time I was trying to figure out what would be the next Mississippi movie. The slate of four films I agreed to direct in MS guaranteed two would be produced in 2017 and two in 2018. The original plan was to make a sequel to Porches and Private Eyes but not quite ready to make that, I pushed it to the Fall of 2018 (last of the slate). Then I tried to write a film about the Witch of Yazoo, a great legend that is definitely movie-worthy. What I wanted to do was sort of like Arachnophobia: suspenseful but with that comedic touch, a Spielberg-esque supernatural thriller. A little ways into the script I lost interest in finishing it when Nick Fornwalt told me he wouldn’t be available to shoot anything in the Fall. This was the kind of film perfect for Nick’s eye and I couldn’t imagine making the film anymore without him. So I went back to the drawing board.

A picture I took of the witch’s grave in Yazoo city.

On a google search for true Mississippi crime tales I stumbled on the Wikipedia page for the Dixie Mafia. What caught my attention up front was the nickname for this criminal group: the Cornbread Cosa Nostra. Before reading much else I thought… a dark comedy. It sounded like something you’d hear in a violent, hilarious Warren Zevon song. I dug deeper and got hooked. Then I spoke with one of the lead FBI agents on the case and his details filled out the rest of my story. A few weeks later and we had a script for the Fall movie, Cornbread Cosa Nostra. This is why I tell folks I’m never sure what I might make next. There are tentative plans but both Blood Country and Cornbread were replacements for other projects. It’s great to get caught by surprise in the writing phase and follow a story all the way out.

To Live and Die in Biloxi

The production of Cornbread is not as easy to put in perspective because there hasn’t been as much distance as Blood Country. Once again, there was a lot happening at once. We premiered our Western in Monticello, Mississippi just a couple days before filming on our crime picture began.

For twenty-five days we shot five days a week with two days off. Most of those weekends for me were taken up by screenings of Blood Country or additional scouts with Jared Kovacs (cinematographer). This time we were tackling another period. Though not as hard as digging up wagons, horses and costumes from the 1800s, it was a challenge to create the 80s in our film. We were again here, there and everywhere in terms of locations: from an alligator farm to a swinger’s club to a rural air strip to a yacht.

We shot the movie chronologically for the most part so that our actors could evolve their looks as the film goes from 1982 to the 1990s. This allowed us to make great adjustments as we went without ruining scenes we’d already filmed but there’s a reason that shooting this way happens rarely in the moviemaking world.

Jared Kovas gets a shot at dusk for Cornbread Cosa Nostra

Two collaborations stick out from this time. One of them is my working relationship with Jared. This would be the second film he shot for me in 2017, the first being Bride. On Cornbread, we found an incredible rhythm, able to share thoughts on everything from lighting to performance. Often, when a take was over, we’d have the same ideas for what needed to change for the next one. Other times, we communicated with ease about our disagreements and even when we didn’t, it was solved in a matter of minutes. The way I work with Jared is quite different than how I work with Nick. Neither is better but just as I couldn’t see making The Witch of Yazoo without Nick, I really can’t see shooting Cornbread Cosa Nostra with anyone but Jared.

The other meaningful partnership that formed during this production was with our leading man, Britton Webb. He wasn’t the first choice for the role. Actually I went through two FBI agent Kurt Cadells before I got to Britton. The other two dropped out for reasons I won’t get into here but just like it took two actors to pass on Casablanca before Bogie stepped in, we got very lucky. Britton played one of the brothers in Blood Country and though he did very well, I don’t think either of us understood each other on set. There was tension but mutual respect. The latter followed us into Cornbread, while we left the former behind, and I have to say that I never enjoyed working with a lead actor so much. The flow of ideas between us, things he wanted to try in scenes and others I wanted, was natural and above all just fun. It made me each day on set all the more exciting, knowing we had such a committed actor in the lead role. I could tell he brought everything he could not only every day but every take. He always wanted to make the movie better and his head was never out of the game. Even if this is the only time we work together as lead and director, I will be grateful that he was our Kurt Cadell.

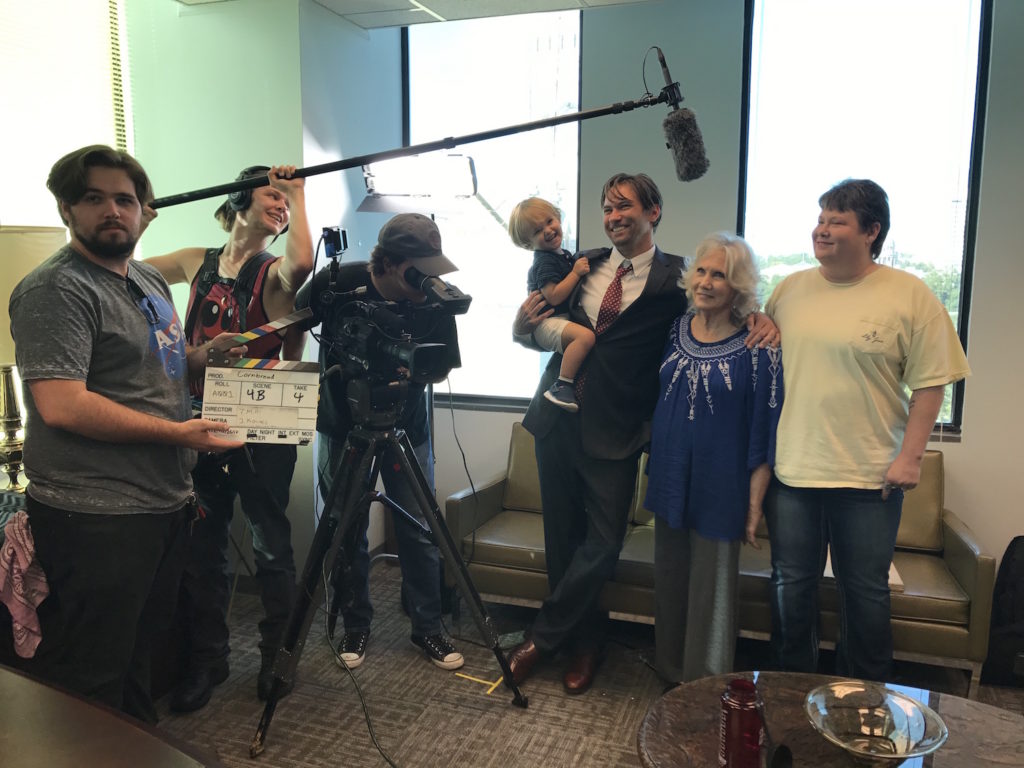

Britton Webb brought his family to set one day.

The rest of the cast was populated by actors familiar in our work and other new faces. Some of them brought everything they had, immersing themselves into the movie, and others didn’t. So it goes, I guess. It wish it wasn’t. Another thing that went the same as Blood Country was an unevenness behind the camera. Regardless of my efforts to fix the issues we had with the crew on that film, we struggled to maintain a balance of work and attitude on this one as well. Not everyone was really a part of that wheel… All I can do is continue to look hard at how our sets run, the people I choose to work with, and my own self to find new ways of making a movie until it feels right, until it’s really the Running Wild I strive for.

A Return to Arizona

Long before Cornbread wrapped, it felt time to take a break from Mississippi. I decided to spend the Winter in Miami, Arizona. Yes, there is a Miami in Arizona. The idea of living a couple months in an old mining town an hour and a half from Phoenix suited me well. I could drive in to have lunch with Gus, go on a date with a girl and hang out with James, but I’d also be off on my own (with my dog Bandit of course). I especially hoped that would be good for writing.

And that has been my focus. I haven’t seen a single scene from Cornbread: Jared handed the footage off to Tony and we have kept our distance from it to have a fresh perspective when he delivers the rough cut, which should be a few days from now. Other than writing and the day-to-day upkeep for the company (social media marketing, planning more showings of Blood Country, accounting, etc.), I found time to finally cut together the documentary I shot in November of 2016 about chili. This film, Fifty Years of Chili, is a short piece I’m fond of. It’s been submitted to some festivals and from there I hope to get it out to the public during 2018.

A shot from Fifty Years of Chili

Another surprise came during the writing phase. I was first working on The Color of Water, a script about famous Mississippi painter Walter Anderson. My approach to this eccentric figure was not a traditional one: I wanted to tell an adventure story about his escape from one of many mental institutions and long walk down to the gulf coast. This would be set in the 1940s and I’d compare it to Tom Sawyer, Huck Finn, Don Quixote and the Odyssey as much as anything else (the last two were apparently influences on Anderson’s own work). Just as I began to really fall in love with the story, I halted the process. My concern became Anderson’s family, very prominent on the Mississippi coast.

Technically from my understanding, Walter Anderson is a public figure and I don’t need anyone’s permission to make a film about him. However, I felt that the film’s success could be hurt if the family was not in favor of it or in any way opposed to it. I took a break from writing to contact them indirectly and the response I received was not the most encouraging. The Color of Walter is not dead but it is dormant. I make independent films the way I do for many reasons. One of them is so that I do not have someone looking over my shoulder, so that I do not have to seek approval of my ideas. That is a necessity, a reality when working within Hollywood or any other organized system. I work as an outsider to tell the stories I want to tell, the way I want to tell them. What you’re seeing on the screen, good or bad, is my intention filtered through the experience of collaborating with tons of others in the process. In the end, it’s not anyone calling the final shot but me. I make films the way I do to preserve that, just as I’m sure Walter did not want anyone telling him what or how to paint.

A funny thing happened a couple weeks ago. Just as unexpected as Blood Country and Cornbread were, another story landed in my lap. I stumbled on the crazy legend from the Civil War of a bullet that struck one soldier in the scrotum and went on to strike a woman in the belly thus impregnating her. I told my dad, “This may be our next movie.” Though I’m sure he thought I was joking (then again he knows I’m crazy), I was quite serious. From the start, so much depth and possibility was evident in this little folk tale. A story surrounding it, its teller and the war emerged in my mind and a completed script followed a week later. It is called Son of a Gun and it is our next feature film to be shot in Mississippi. This is what I love most about being a filmmaker: whether on set or behind a computer, when an idea takes hold in the spur of the moment and we go with it. And that is where I am now, ready for another film adventure and another year of Running Wild.

There are so many more stories to tell just from this year. Some have been left out because I doubt you want to read a novel, others should remain unknown for now. Perhaps one day they’ll be told as well.

As I near the end of this retrospective, my thoughts return to the truck. Every time I look at the dented roof, busted window, missing mirror and broken taillight, I see how close we came. If we’d crashed a couple hundred yards before, where the median follows a steep slope into trees, we’d probably be dead. The truck, which seemed to be at its end, has continued on for months now. The truck is like me, like Running Wild. Battle wounds and all, it runs. I’m grateful for every day I get to drive it. I’m grateful for every day I’m alive and get to make movies.

-Travis Mills

This is really an amazing story of your year Travis. You have been going non stop and have achieved so much with determination and belief in what you are doing and your vision. You were so lucky in that accident for sure God was watching out for you and did the right thing to just pick and keep on going! It was really nice to read all the behind the scenes that occurred in making your films and the inspiration for them. I enjoyed being a small part of Blood Country and Cornbread and I can’t wait to see my scene when the movie comes out in May. Looking forward to having you back in Miss for Son of a Gun. Keep that truck rolling and your dog Bandit by your side!

Thank you, Damon, for reading this and being a part of what we’re doing.

Wondering what you’re going to do in New Mexico and where in NM?

Hi Sue. As I replied on Facebook, that has yet to be determined. These Westerns will be shot in 2020 so we are in the early stages of figuring all that out.

Travis, you’re the best director I have ever worked with on a film. (Inside Joke for everyone else)

haha, good one! Thanks Joe